A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE (CSA) LEGAL FRAMEWORKS IN SOUTH ASIA: POLICY IMPLICATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTION FOR COUNTRIES

By Shayana Satpathy, Student, Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law, Punjab

Email id: shayanasatpathy1512@gmail.com.

&

Dr. Sujata Satapathy

Professor of Clinical Psychology, Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS).

Email id: dr.sujatasatapathy@gmail.com.

I. INRODUCTION

Child sexual abuse (CSA) constitutes a profound infringement on the fundamental rights of children, with significant adverse effects on their survival; and physical, emotional, and psychosexual development; physical health; and socio-legal fabrics of a country. A country’s CSA specific legal framework reflects its seriousness and sensitivity towards the country's standing in protecting fundamental rights of a population segment which is politically less relevant, physically and economically totally dependent, emotionally less competent, socially at the bottom of the power hierarchy, and health wise susceptible. In presence of non-specific legal approach towards CSA, the risk of abuse is multi-fold and vulnerability to lack of accessibility and availability of protection of and justice to their rights is high.

In the South Asia region (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka), CSA is pervasive. As these countries are geographically connected, the similar/dissimilar legal frameworks could have larger implications on intercountry child trafficking, child marriage, child pornography content preparation and marketing, violence against children, and child labour. Geographical proximity also influences socio-political and cultural dynamics of the countries. Therefore, it is important to analyze the commonalities and differences in the CSA legal frameworks of the South Asian countries.

Globally, 650 million (1 in 5) young girls have been subjected to sexual violence during their childhood. In contrast, globally, an estimated 410-530 million (1 in 7) young boys have been victims of sexual violence. The largest number of victims have hailed from the most densely populated areas around the globe. Namely, South, Southeast and Central Asia in addition to Sub-Saharan Africa.[1] In accordance with research conducted in 2016, a minimum of 50% or more of children aged 2–17 in Asia, Africa and Northern America – or over 714 million children and that globally over half of all children—1 billion children have experienced at least one form of severe violence including severe physical violence, emotional violence, sexual violence, bullying, or witnessing violence.[2]

South Asian nations have undertaken initiatives to combat CSA directly or indirectly through legislative reforms; however, challenges in the implementation of said legislations continue to persist. Most of the countries have also enacted legal provisions, though the consistency in enforcement of these provisions remains factorially variable. Notwithstanding these legislative measures, entrenched societal obstacles such as victim-blaming, insufficient public awareness, and inadequate law enforcement continue to hinder progress. Numerous cases of CSA remain unreported due to fears of shame, social ostracism, and a lack of confidence in the judicial system. Therefore, the effective implementation of existing laws, coupled with ongoing societal transformation, is critical for the prevention of CSA and the attainment of justice for survivors. Addressing CSA in South Asia necessitates not only robust legal frameworks but also community-led initiatives that emphasize child safety and foster a culture of protection and accountability for offenders. And identifying the current status and sharing of learning from best legal practices ultimately will reduce child trafficking, child pornography, CSA, child marriage, etc. in the region.

II. METHODS

Search Strategy

An open electronic search (without specifying filters such as publication date, text availability, article attribute, and article type) was conducted for Global Databases, namely, PubMed, HeinOnline, UN Digital Library, ECPAT Global Database, OHCHR Database, NATLEX and Local Databases, namely, India Code, NCRB, India, Manupatra, NCWC Bhutan, Shocheton, Child Sex Offenders Registry Maldives.

Keywords Searched

The search used keywords such as child protection Act, child rights protection law, CSA Act, punishment for CSA act, law and child sexual abuse, legal frameworks for CSA, courts for CSA, punishment for CSA perpetrator Act, CSA cases records, CSA special courts, CSA pending cases, mandatory reporting of CSA, monetary compensation for CSA victim, justice delivery system for CSA, and conviction rate for CSA cases. With each key word, the country name was either suffixed or prefixed.

Study Selection

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were broadly followed. A paper/record/document/publication which met the following inclusion criteria was included:

1. A legally valid document e.g. Act/Bill/Policy/Gazette etc. on CSA

2. Documents in English

3. Full length papers/documents on child rights, child protection, child marriage, child sexual abuse, or child abuse.

4. Annual crime report of a country or country specific crime against children report

5. If the full or part of the paper/document was concerned about children aged below 18years

Documents such as abstract in the conference, editorial, letters to editor, unpublished dissertations/theses, leisure articles in magazines, etc. were excluded from the analysis.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

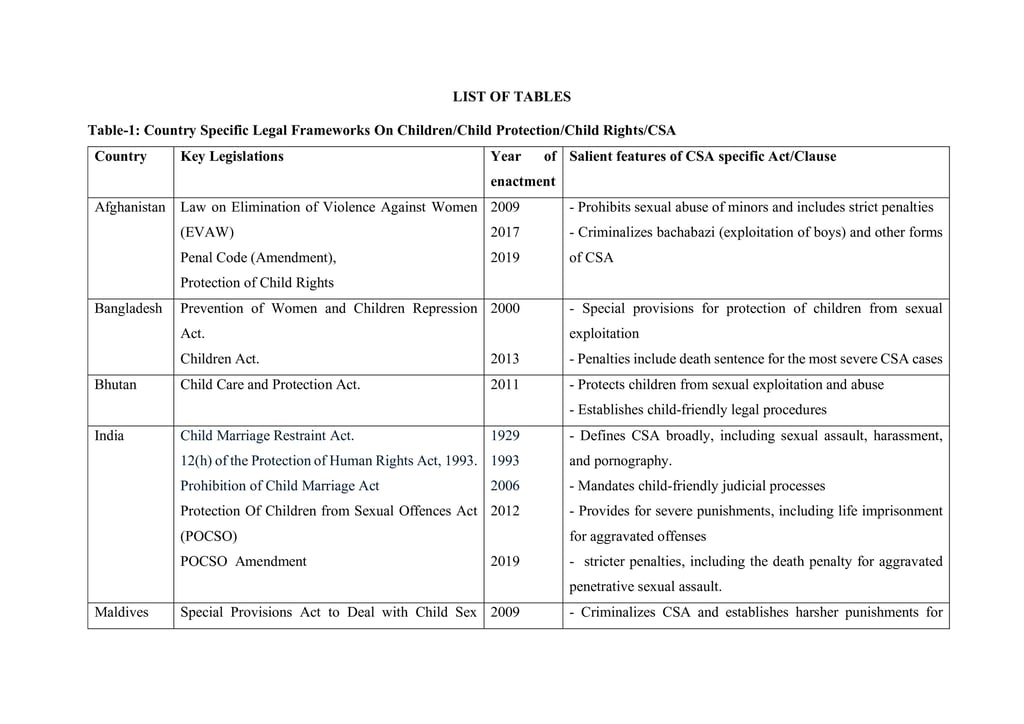

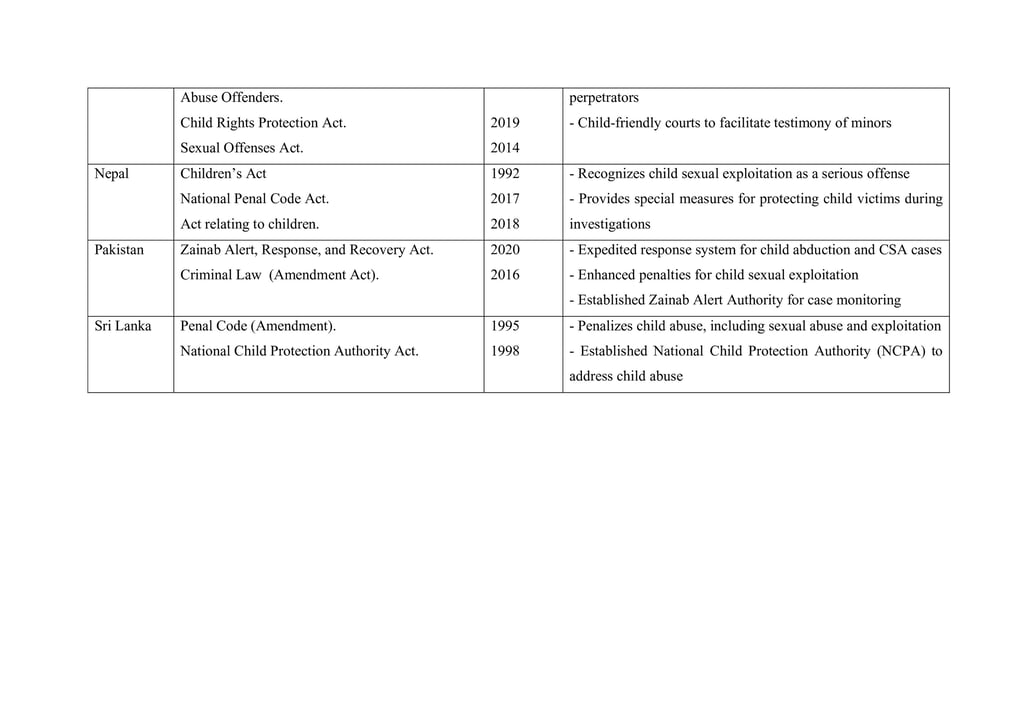

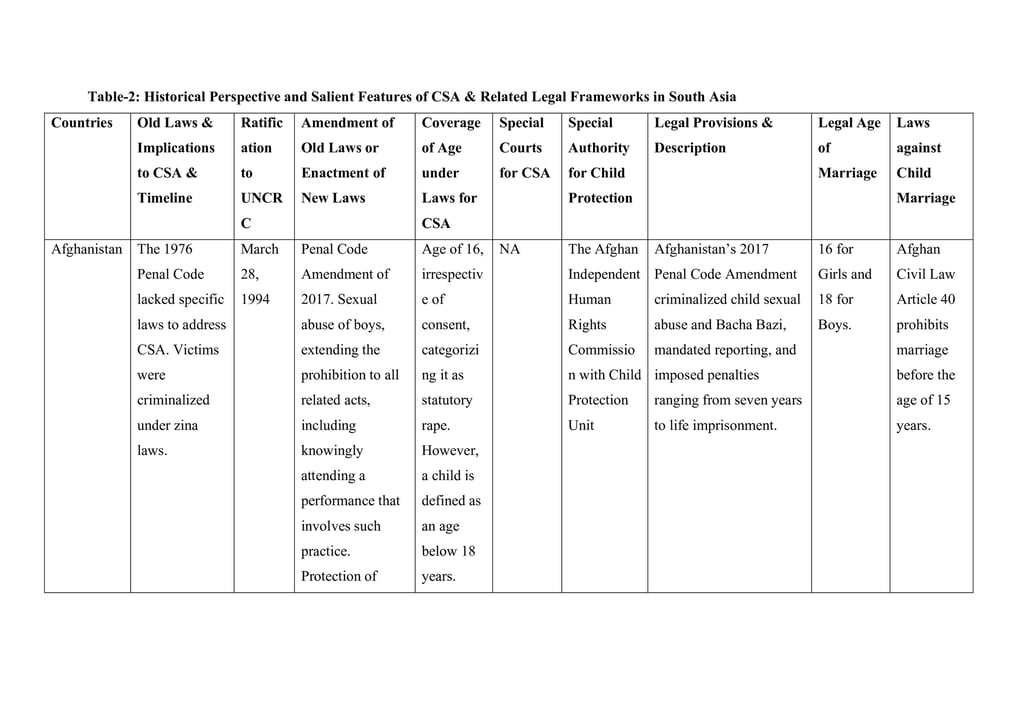

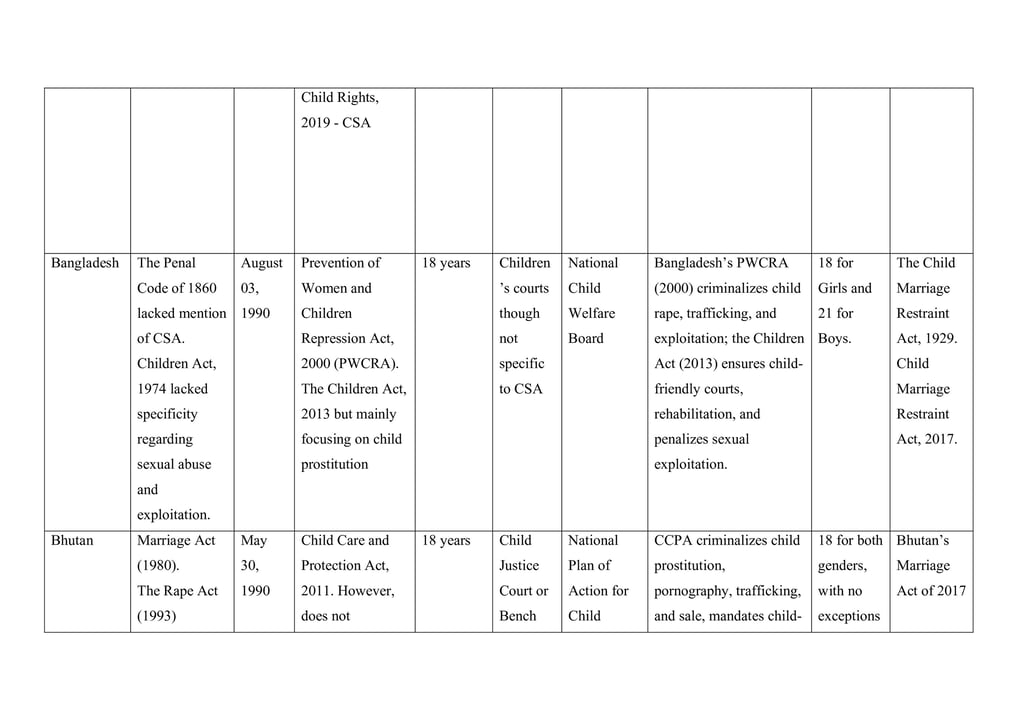

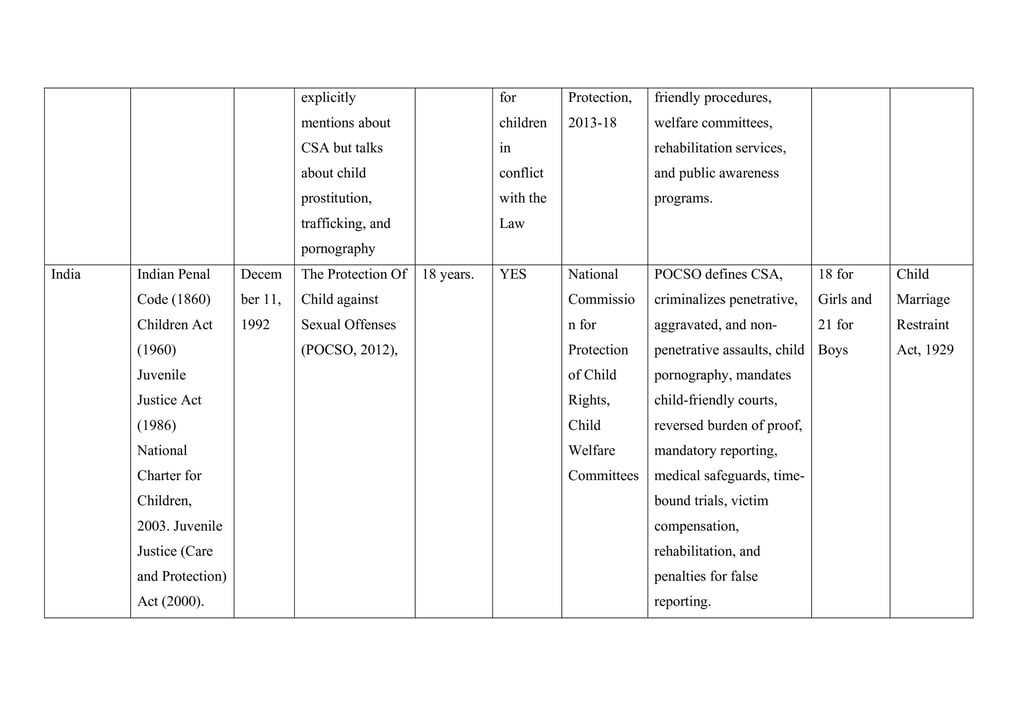

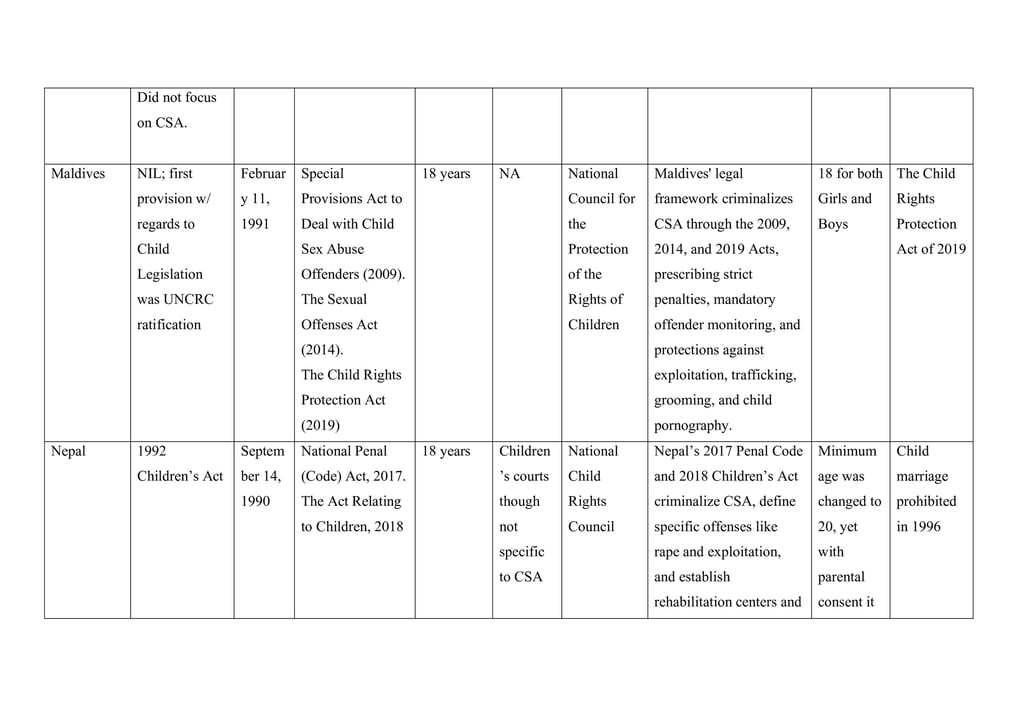

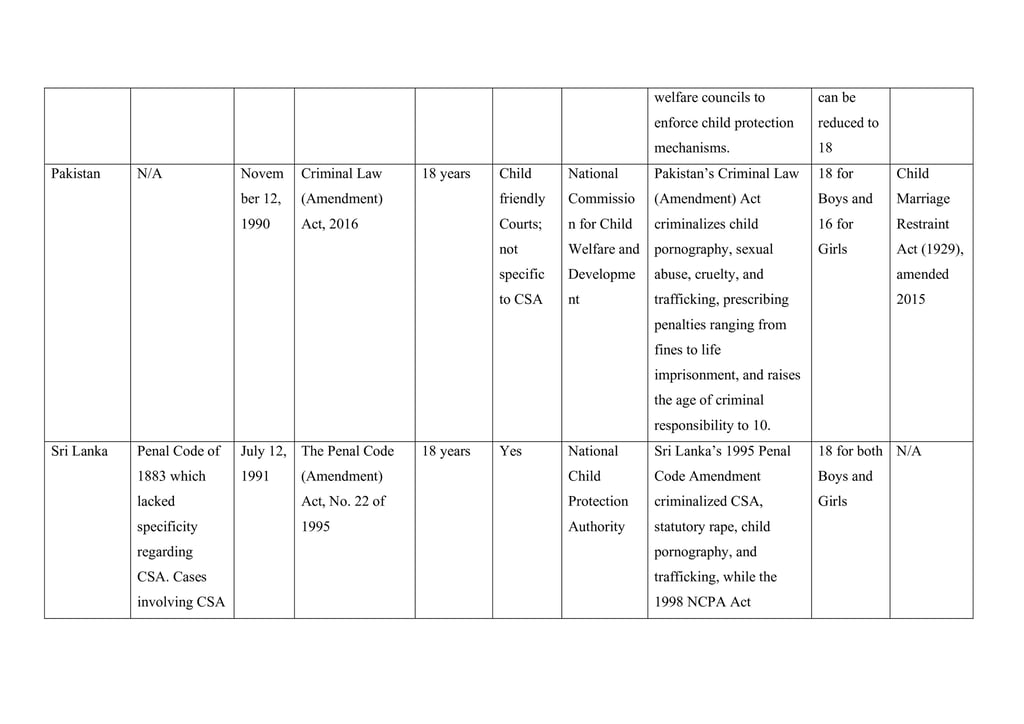

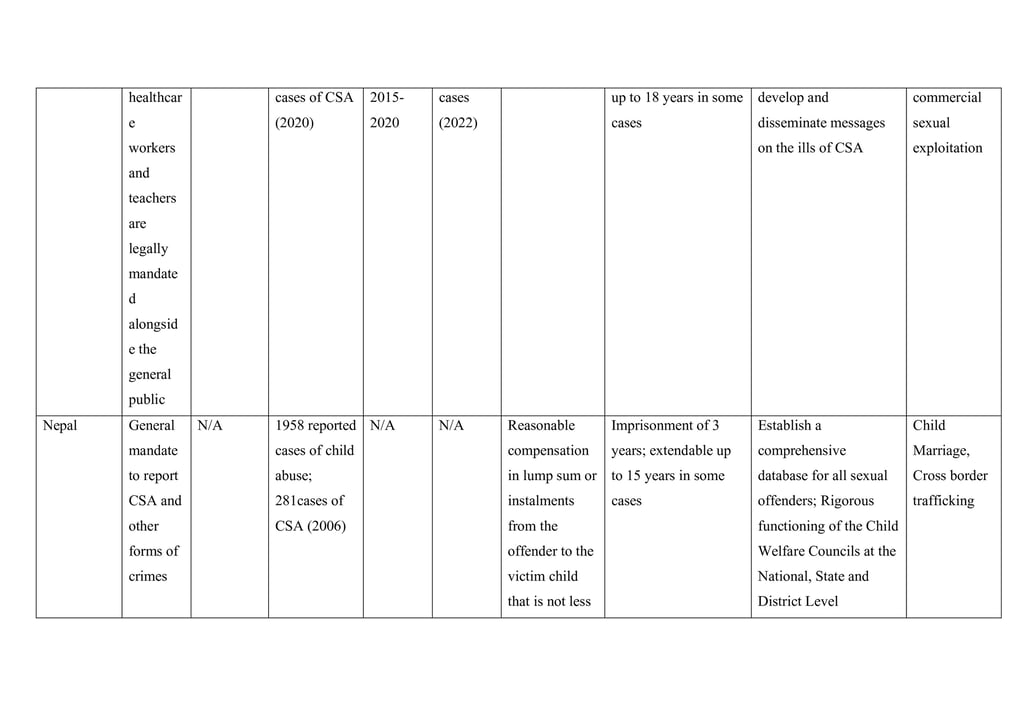

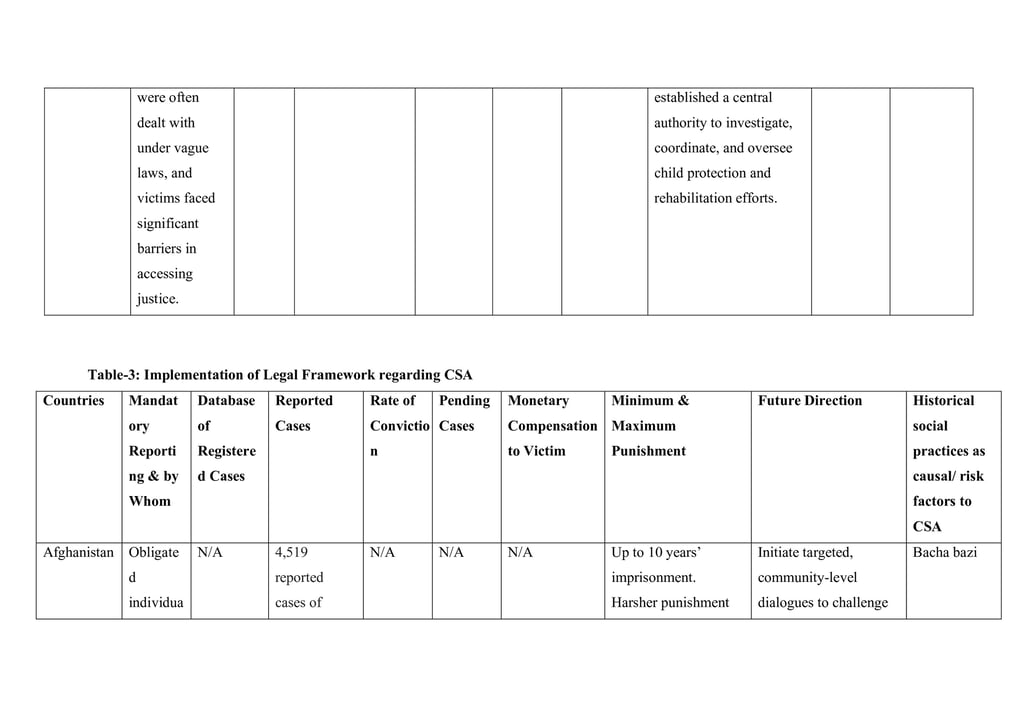

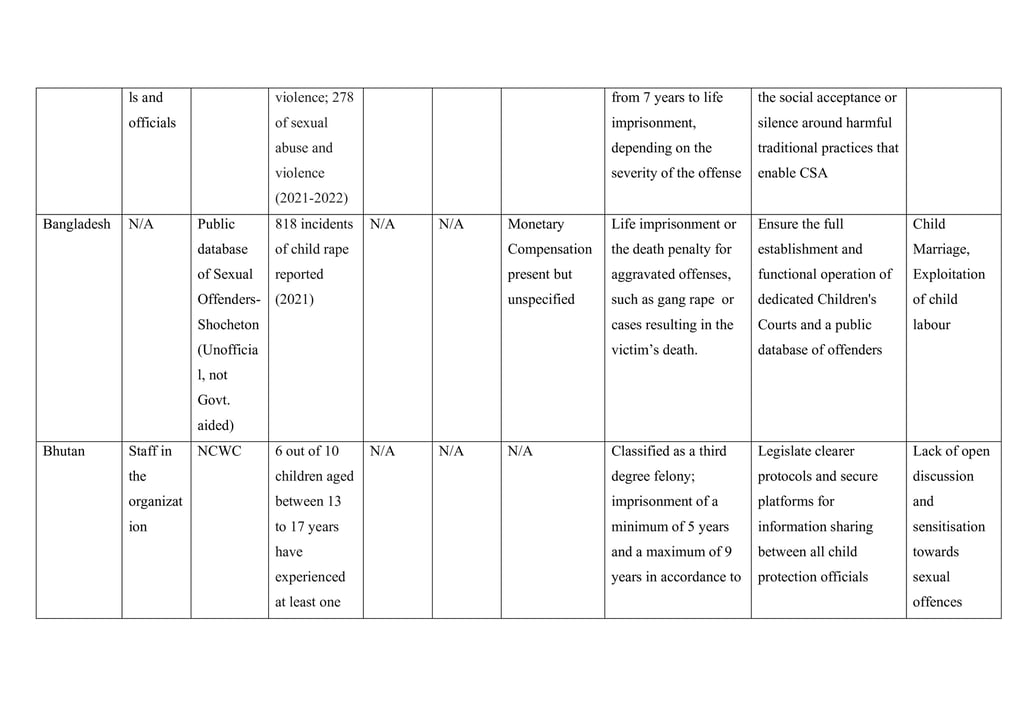

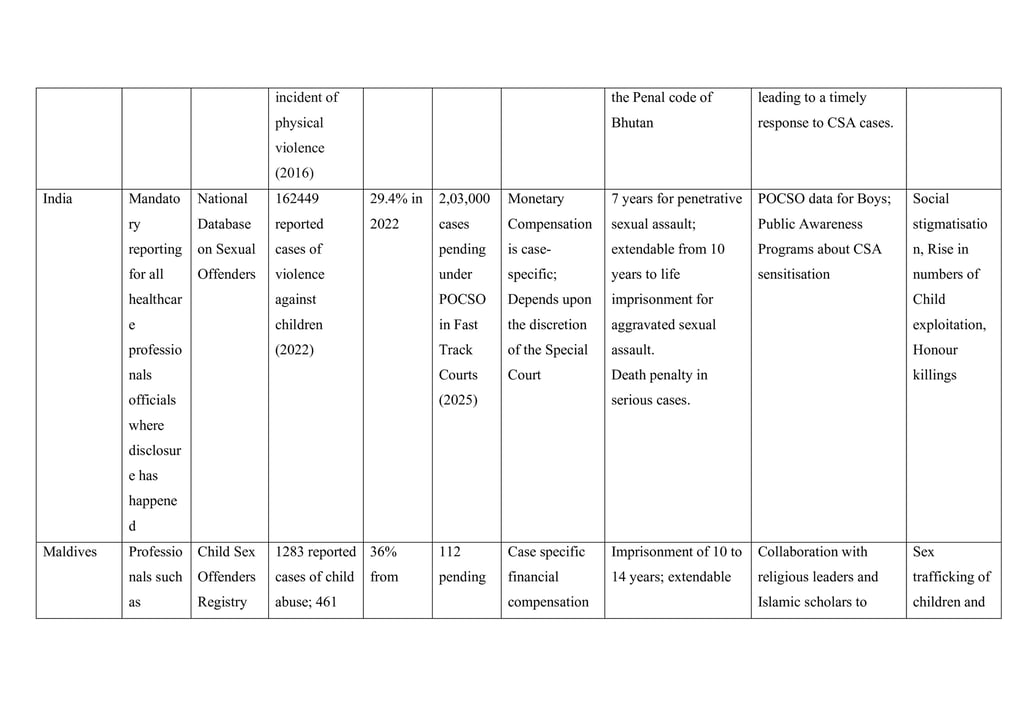

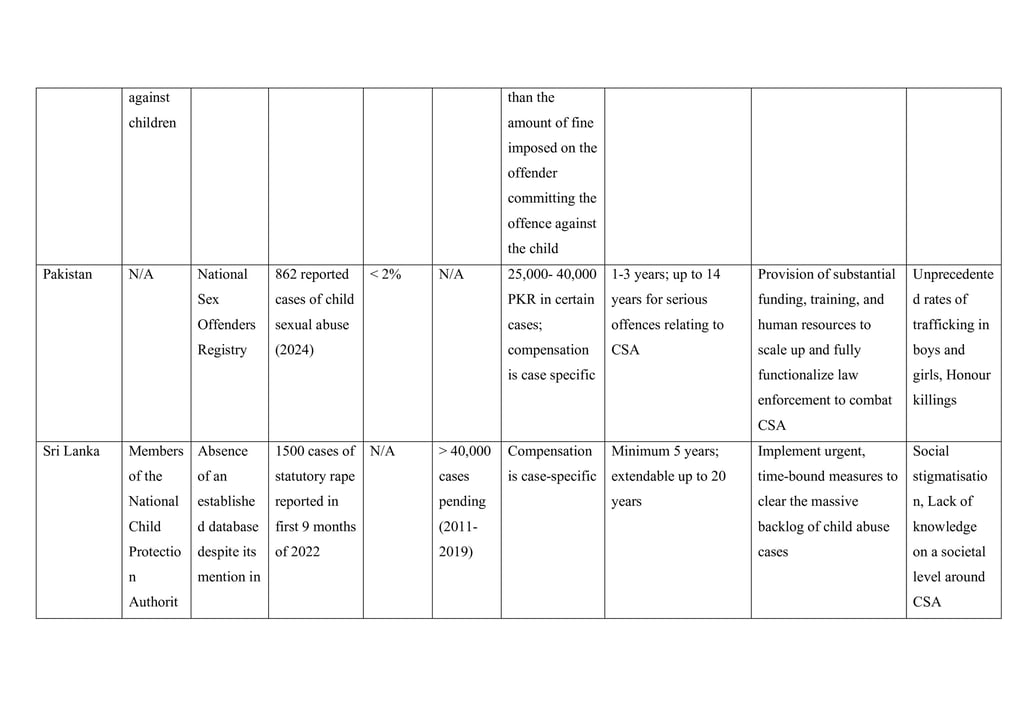

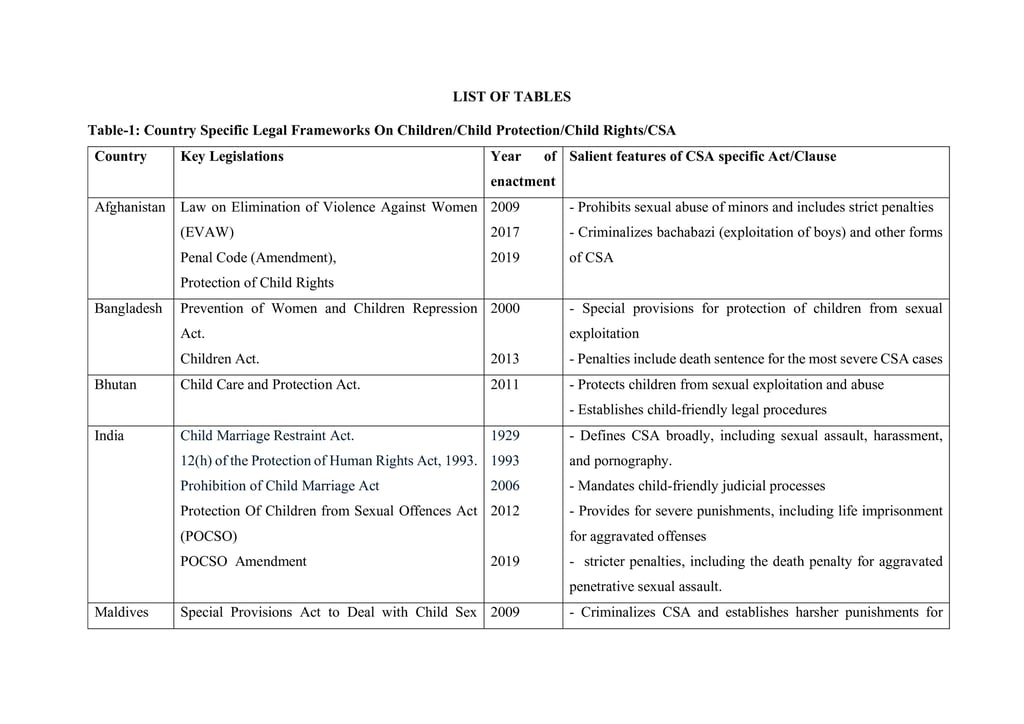

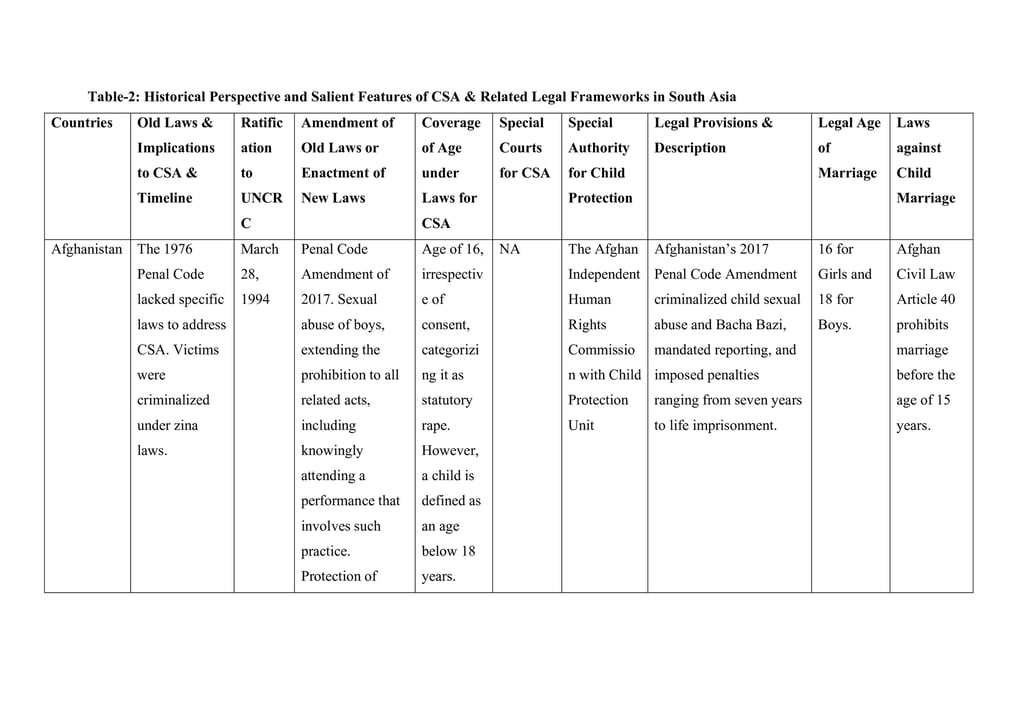

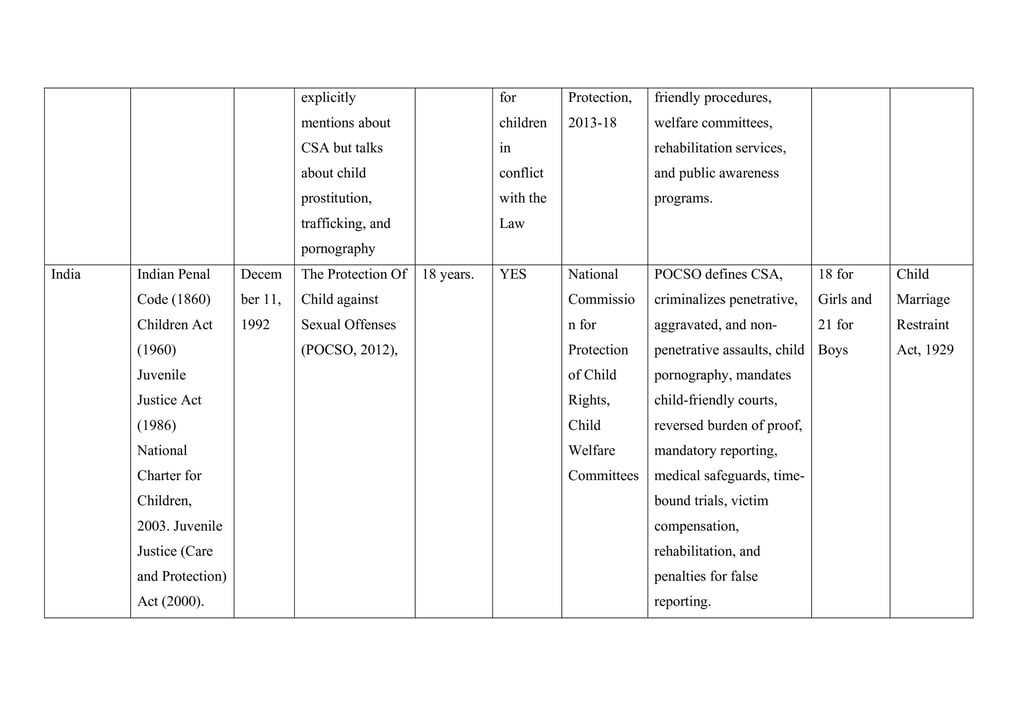

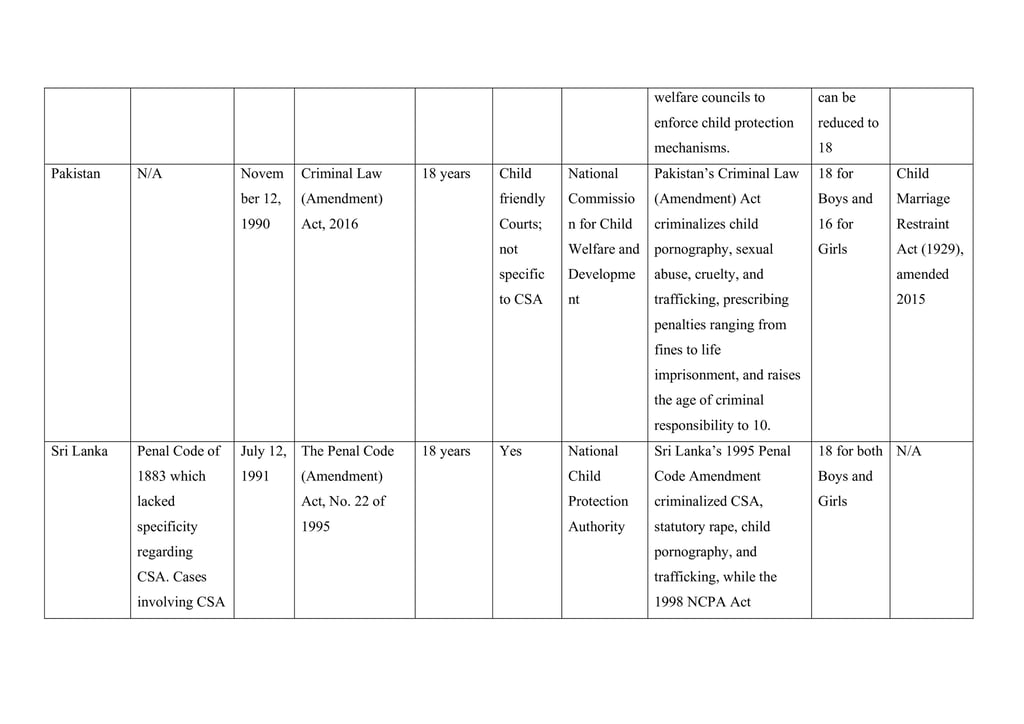

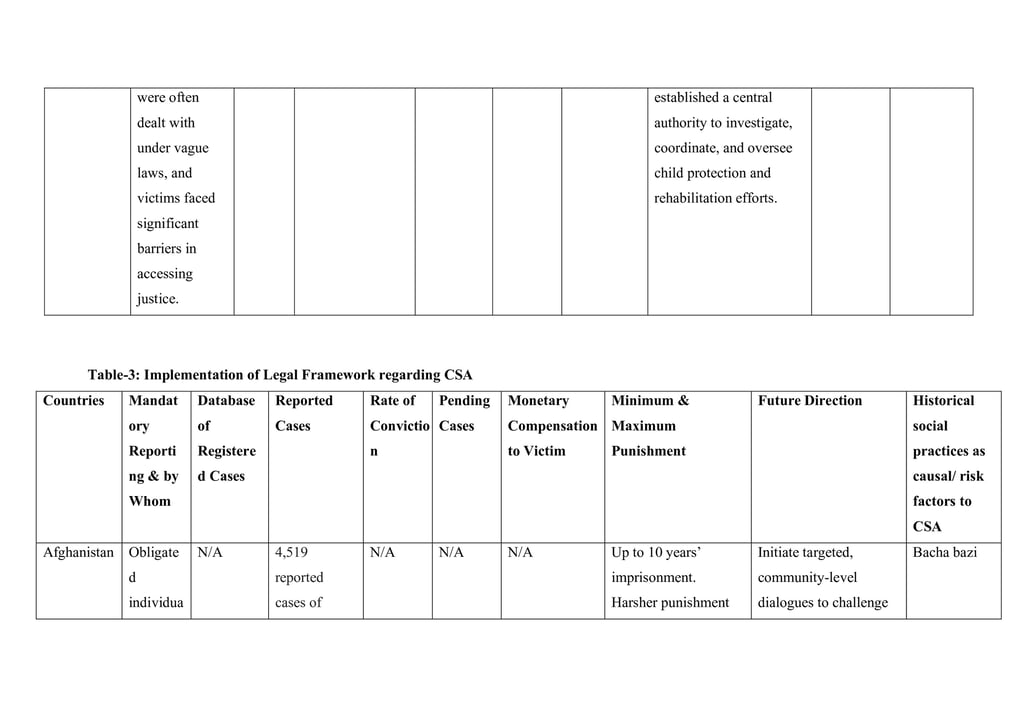

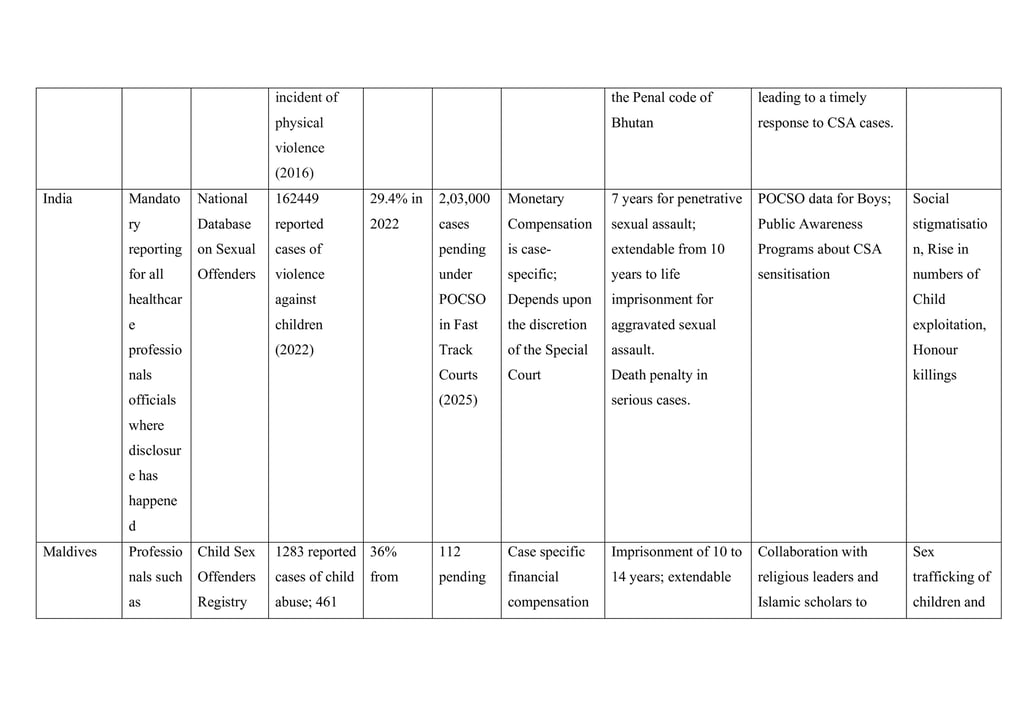

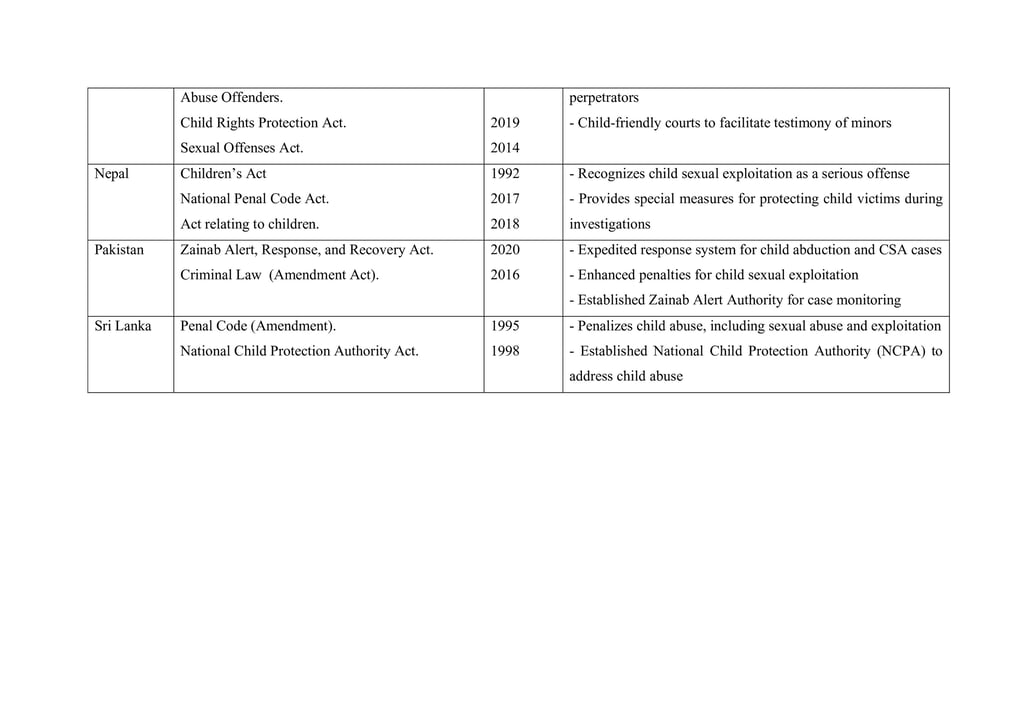

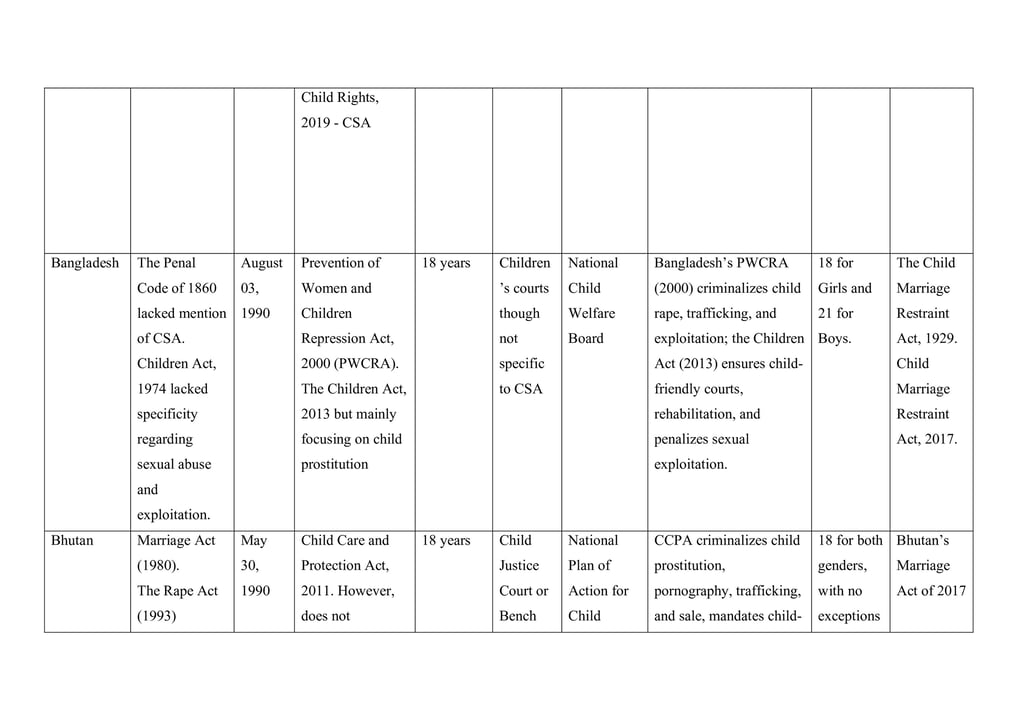

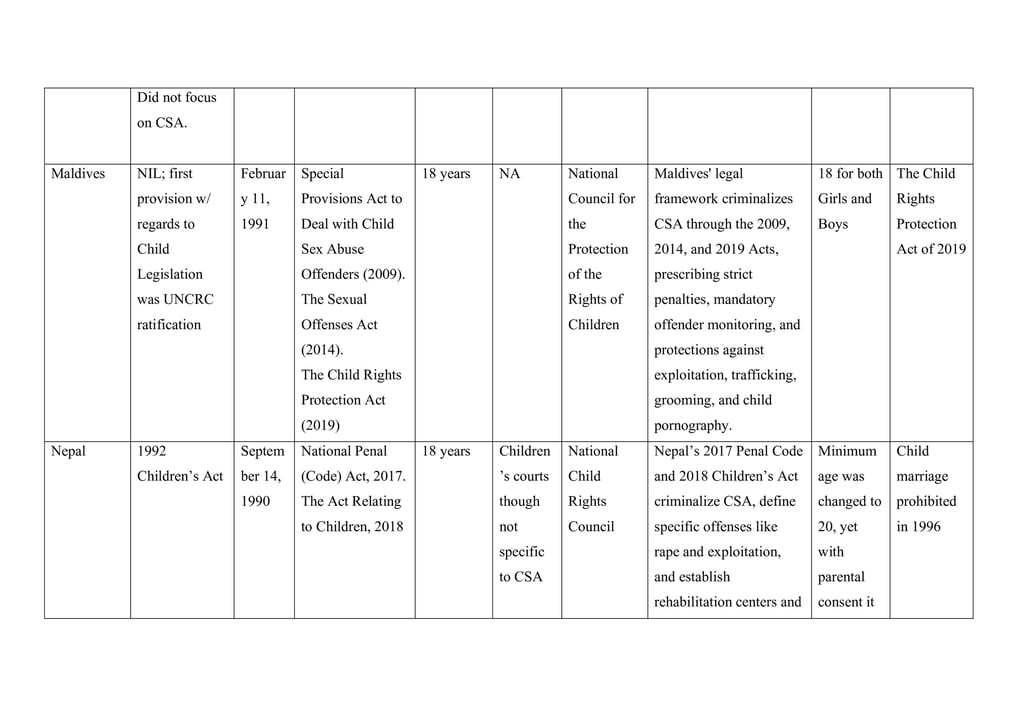

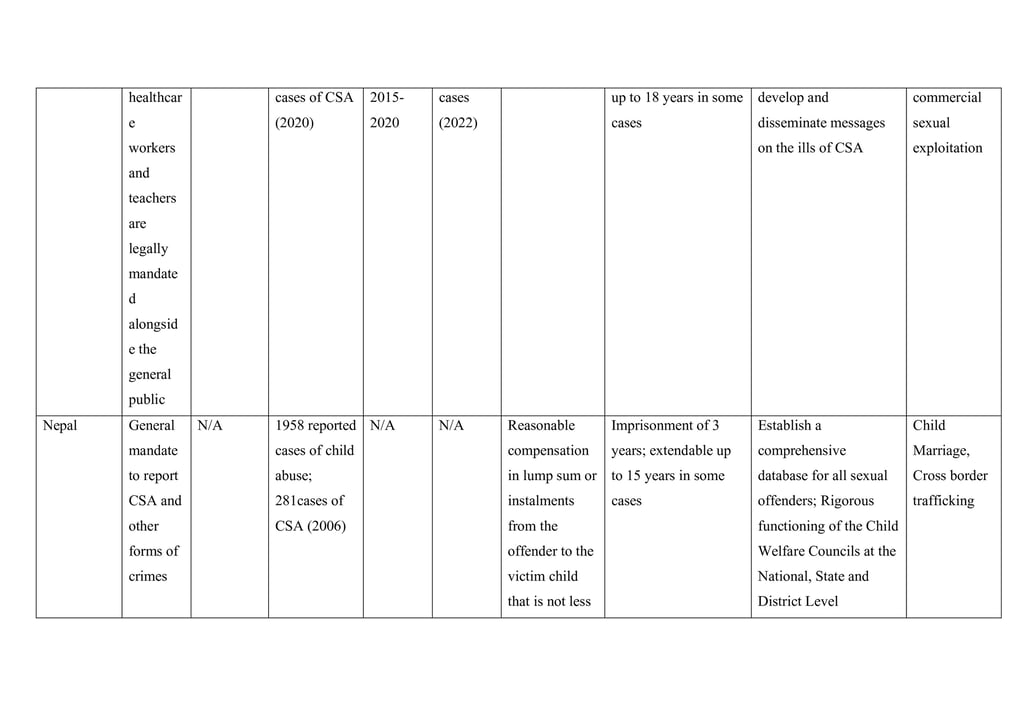

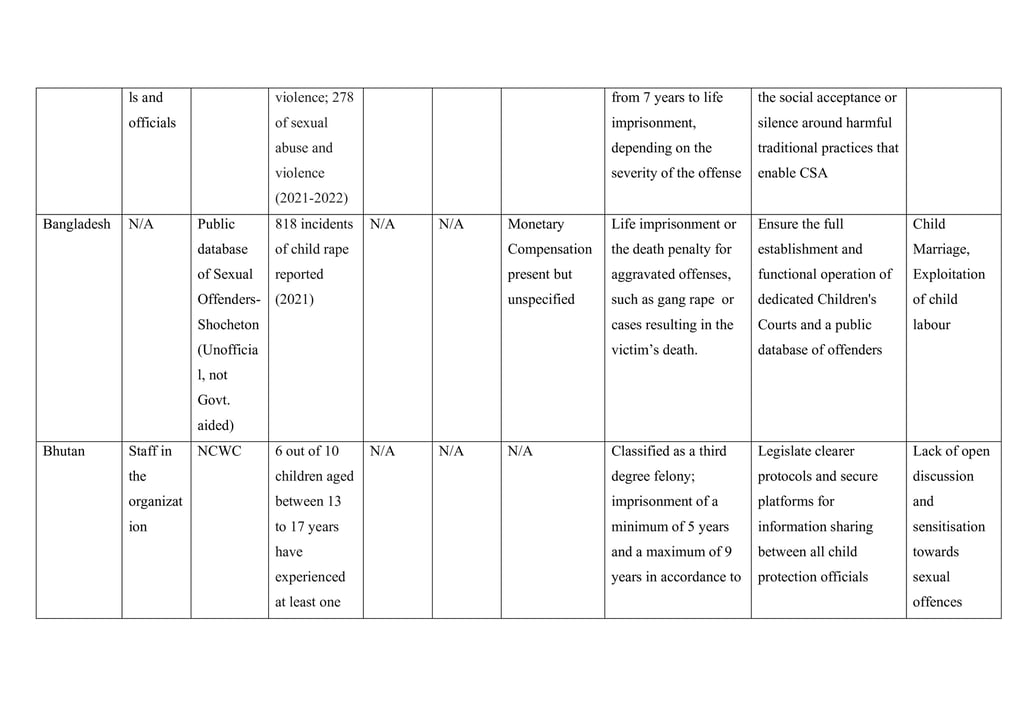

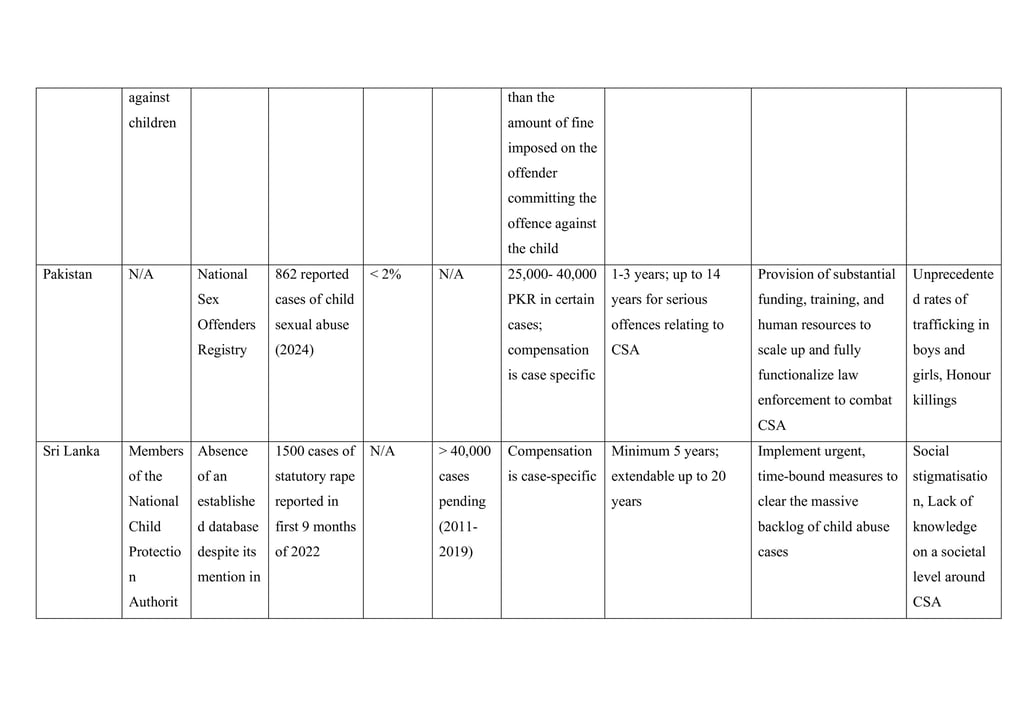

The data was exported to an excel sheet and then organized into theme specific tables. Table-1 presented data on CSA related legal frameworks of each country, year of enactment, and salient features of the Act. The Table-2 displayed relevant information on old laws & implications to CSA & timeline, ratification to UNCRC, amendment of old laws or enactment of new laws, coverage of age under laws for CSA, special Courts for CSA, special authority for child protection, legal provisions & description, legal age of marriage, and laws against child marriage. Similarly, Table-3 highlighted specific information on mandatory reporting & by whom, database of registered cases, reported cases, rate of conviction, pending cases, monetary compensation to victim, minimum & maximum punishment, future direction, and historical social practices as causal/ risk factors to CSA. Due to lack of data availability number of reported cases and pending cases, and rate of conviction related information is year specific for some countries. As legal documents were largely included, a quality assessment was not done.

III. RESULTS

A total of 19830 records were found from all databases out of which 19790 were excluded due to duplication (N=4075), other country documents (N=3987), incomplete (N=3222), non-English language document (N=1671), abstracts (N=6000), and source documents or no mention of author of the document (N=835 ). A total of 37 articles were included for the final analysis.

The oldest laws having some specific provision for children dates back to Indian Penal Code (1860) which was adopted by Pakistan and Bangladesh later on, and Sri Lanka’s Penal Code (1883).

Country specific legal frameworks on child marriage/child protection/child rights/CSA

The definition of CSA also remains by and large the same with some variations in detailing the terminologies and contexts. Except the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO, 2012) of India, the extensive definition of different kinds of CSA is not provided in the legal documents of other countries. As reflected in Table-1, the Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929 of India is the oldest legal framework which indirectly targeted curbing CSA to allow children (especially girls) to develop to their fullest with a mature body to sustain child birth. This was the first move in the region to protect children’s right to survival and health, although CSA was not the conceptually strong and outlined in this Act. However, the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006 of India more prominently mentions about CSA and children’s rights to be protected from it.

Similarly, the Zainab Alert, Response, and Recovery Act, 2020 of Pakistan is the most recent one in CSA legislature in the region. Further Sri Lanka is first country in South Asia to enact laws on child protection (National Child Protection Authority Act, 1998) followed by Maldives, Bhutan, India, and Bangladesh. Nevertheless, Nepal had its Child Act in 1992, however protection from CSA was not explicitly addressed. Afghanistan is the only country which doesn’t have a child specific Act and children term mentioned in the title of the Act. Children are still tagged along with the women in legal framework of Afghanistan and Bangladesh. Interestingly, Maldives is the only country that has a dedicated Act for CSA offenders, namely, Special Provisions Act to Deal with Child Sex Abuse Offenders, 2009. Laws of majority of countries address criminalization of CSA, child friendly legal procedures, gravity of offenses and commensurate punishments, protective measures for children during investigation, and procedure of medical examination. Legal ban of social practices (e.g. bacha bazi) related to CSA has explicitly been mentioned in Afghanistan’s Law on the Elimination of Violence Against Women (EVAW), 2009 and the Penal Code (Amendment) Act of 2017. The social belief that sexual intercourse with younger children enhances longevity and sexual potency is not uncommon in South Asia, however, the current status of prevailing beliefs regarding the same and social practices needs to be explored.

Historical Perspective and Salient Features of CSA & Related Legal Frameworks in South Asia

The congruence between child marriage prohibition laws, legal age of marriage and child right/protection laws is very important for a country. As an expansion of Table-1, Table-2 threw light on the small discrepancies and incongruence in age coverage under different laws of the countries. E.g. Although the defining age of a child is 0-18 years in the South Asia region, the age of marriage is ≥ 18 years in all countries except Afghanistan (16 years in Penal Code Amendment Act, 2017 and Protection of Child Rights Act, 2019) and Pakistan. In fact, Afghan Civil Law Article 40 prohibits marriage before the age of 15 years. Interestingly, The Act Relating to Children, 2018 of Nepal (Child marriage was prohibited in 1996) mentions the minimum age of marriage was changed to 20, yet with parental consent it can be reduced to 18. Legal validation of parental consent in marriage and power of family in deciding marriageable age (of course staying within the purview of law) reflected the impact of socio-cultural practices. Further, as Bangladesh was created in 1971, the Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929 of India was also in place for Bangladesh, which was modified in 2017 (2006 in India).

All countries have special authority for child protection however, special courts for CSA cases disposal were not available in Afghanistan and Maldives. Maldives might not need it perhaps due to a smaller number of cases reported (small population size and low density).

Implementation of Legal Framework regarding CSA in South Asia (Table-3)

Mandatory reporting is specified for all countries; however, Bangladesh and Pakistan are lagging behind. Legal consequences of failure in not reporting still lacks clarity and the specific professionals/authority is mostly accountable in majority of countries. The laws in most countries are either silent or not specifying the role of parents in mandatory reporting. Absence of an established database was noted despite its mention in the NCPA Act of Sri Lanka. Nepal and Afghanistan have no public data bases for CSA cases reported. Similarly, while monetary compensation to the victims is featured in the law, Afghanistan and Bhutan don’t specify anything.

A general trend of non-availability of data on conviction rate, average punishment, compensation by the government and the accused, pending cases, mean age of the victims etc. was noted. Social stigmatization, honor killing and cross border trafficking were the pressing issues highlighted in all legal frameworks, however, the data base on trafficking doesn’t have specific data of prevalence of CSA amongst the recovered cases. Urgent and time bound disposal of pending cases was imminent for India (despite having time-bound trial and special courts) and Sri Lanka. Amount of punishment varied between 1 year (Pakistan) to 20 years (Sri Lanka) to life imprisonment (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India). However, Sri Lanka and Bhutan defined the minimum punishment as 5 years, while Bhutan specifies the maximum as 9 years and Bangladesh and India provisioned death penalty in aggravated sexual assault cases. How to deal with false reporting and the legal consequence was also a key gap.

IV. DISCUSSION

Subsequent to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Children (UNCRC, 1989) ratification, almost all countries enacted new Acts/laws for CSA/child protection or amended the existing legal frameworks in different ways and to varying degrees to be aligned with the UNCRC. All South Asian countries have made significant progress in implementing the UNCRC's provisions, including increasing: applicable laws, public budgets, child rights supportive social beliefs, civil society commitment, youth awareness and self-confidence, legal redressal mechanisms and infrastructure, punishment to the offenders, and policies.

Also, abolishment of legal frameworks related to restraint/prohibition of child marriage played a solid role in curbing CSA significantly in a legal way, although UNCRC has great concerns regarding practice of child marriage in Bangladesh, Nepal and Afghanistan (UNICEF, 2019).

Country Specific Legal Provision for CSA as a Stand out Law

India notified the Protection of Children from Sexual Offenses (POCSO) in November 2012, prior to which CSA cases were addressed under general provisions of the Indian Penal Code (IPC, 1860), such as sections on rape, molestation, and outraging the modesty of women. These laws, however, proved insufficient, as they did not define or address non-penetrative abuse or abuse against boys specifically. POCSO provided a structured framework for reporting, investigating, and prosecuting CSA, with specific protections for child victims and severe penalties for perpetrators. The subsequent amendment (2019) introduced stricter penalties, including the death penalty for aggravated penetrative sexual assault. India defines Penetrative Sexual Assault (Section-3), Aggravated Penetrative Sexual Assault (Section-5), Sexual Assault (Section-7) very clearly followed by Bangladesh as compared to other countries. The POCSO clearly spells out provisional specificities such as child pornography (Section-13), mandatory reporting (Section-19-20), medical examination (Section-27), statement recording (Sections-24-26), burden of proof on the accused (Section-29), special courts (Section-33), victim compensation (Section-33(8)), time bound disposal (Section-35), in camera trial (Section-37), special provisions for disabled children (Section-39), victims rehabilitation (Section-40), and false reporting (Section-22 with imprisonment of 6-12 months with fine). Such specificity was missing from the legal documents of other countries.

Pakistan’s Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, March, 2016 was a result of a massive child abuse scandal (August 2015) emerged in Kasur, Punjab, where a gang was found to have exploited over 280 children from 2006-2014. The perpetrators documented the abuse in 400 videos, using the footage for blackmailing the families of the victims. The clips were also distributed across the district for monetary benefits.[3] The Act emphasized on criminalization of child sexual abuse (Section-292A: Sections-377A & 377B for sexual abuse below 18 years), defining the boundaries of and penalties for child pornography including its production and distribution (Section-292B: up to 7 years imprisonment and fine), and addressing the trafficking of minors. Some unique provisional specificities are punishment for addresses possession of child pornography (Section-292C); cruelty against children, including assault, ill-treatment, neglect, or abandonment (Section 328C:14 years to life imprisonment for serious offenses); age of criminal responsibility (minors aged 10-14 may be held responsible if deemed mature) and other judicial discretions.[4]

The Penal Code Amendment (2017) of Afghanistan marks a watershed in the country's legal history by explicitly criminalizing CSA and a deeply entrenched Bacha Bazi social practice in certain parts of Afghanistan, involving the sexual exploitation of young boys who are often forced to dress as girls, dance, and perform for male audiences.[5] Before this reform, Afghanistan’s legal framework (Penal Code, 1976) was inadequate, with vague or nonexistent provisions against these crimes, leaving countless children vulnerable to abuse, coercion, forced labor and exploitation. Even the victims were criminalized under zina laws (prohibiting illicit sexual relations), requiring them to prove coercion to avoid punishment. The United Nations and Human Rights Watch report on prevalence of CSA and Bacha Bazi (especially within warlords and tribal leaders),[6] NATO forces documentation on instances of CSA within the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF),[7] inquiries by the U.S. Congress,[8] and intensive advocacy efforts by civil society organizations [9] were the key role players in this Amendment Act. Although not very specific like India and Pakistan established sentences range from 7 years to life imprisonment, depending on the severity of the offense. However, following the Taliban’s return to power, the enforcement of child protection laws became inconsistent, [10] with reports indicating uneven accountability and limited formal legal proceedings against offenders.[11]

Sri Lanka’s Penal Code of 1883 provided general provisions for offenses like rape and abduction, without specificity to CSA. Its legal frameworks for addressing CSA namely, the Penal Code (Amendment) Act, No. 22 of 1995,[12] and the establishment of the National Child Protection Authority (NCPA) under Act No. 50 of 1998 [13] laid the foundation for addressing CSA and child exploitation. CSA was explicitly recognized as a distinct criminal offense, covering acts such as rape, sexual assault, and other forms of sexual exploitation involving minors. The amendment criminalized acts of sexual intercourse with a child under the age of 16, irrespective of consent, categorizing it as statutory rape. Sexual exploitation of children for commercial purposes, such as trafficking and prostitution, was explicitly penalized. Producing, distributing, or possessing child pornography became punishable offenses. Harsh penalties were introduced, with terms of imprisonment ranging from 7 to 20 years for aggravated offenses involving minors. The NCPA monitored the implementation of laws related to CSA and served as a coordination hub between law enforcement, judicial authorities, and child protection agencies. The UNCRC and UNICEF[14] provided impetus to enact the Penal Code (Amendment) Act, No. 22 of 1995, NCPA Act, No. 50 of 1998 and its initiatives to train law enforcement officers and judiciary personnel on handling CSA cases sensitively,[15] special courts,[16] and establishing a national legal database for tracking legislation and offenders. [17]

The legal framework addressing CSA and exploitation in Bangladesh has significantly undergone multiple facets of evolution, with key milestones including the enactment of the Prevention of Women and Children Repression Act, 2000 (PWCRA) and the Children Act, 2013. There are 34 sections and they are divided into three parts. The first part includes a short title, definition and supremacy of the Act, the second part is about punishments for perpetrators, and the third part is about trial, procedure, investigation, cognizance, jurisdiction, appeals.[18] Section-9 specifically defines and penalizes rape, with aggravated penalties including life imprisonment for child rape.[19]

While Section-5 outlines severe penalties ranging from life imprisonment for child trafficking for sexual exploitation, and life imprisonment or the death penalty for aggravated offenses, such as gang rape as defined in Section 9 (iii) or cases resulting in the victim’s death. The Children Act, (2013) also defines a child as any individual under the age of 18 instead of 14 years.[20] The Act criminalizes all forms of sexual exploitation and abuse of children (Section-80); establishes special child-friendly courts, child welfare boards (Section 8), and child development centers (Sections-84-85, 87), child pornography, children’s tribunals in each district, and a task force for cross-border trafficking of children.[21] A recent report on the legislative and implementation gaps concerned with the trafficking of children by ECPAT (End Child Prostitution and Trafficking) was key to recent changes in the act.[22]

Bhutan's legal framework for child protection has evolved significantly, culminating in the enactment of the Child Care and Protection Act 2011 (CCPA) [23]focusing on the establishment of a standardized child justice system and a comprehensive legal framework with provisions that effectively address all aspects concerning children, ensuring alignment with the evolving economic, social, and cultural landscape of the country Chapter 2, Section 15 (a). The unique provisional specificities were sale of children (Section-221), child prostitution or any unlawful sexual practice (Section-222), use of children in pornographic performances or materials (Section-223), trafficking (Section-224), community participation to rehabilitate children (Section-31-34), closed facilities and aftercare homes for stabilizing children (Sections-51-52), constitution of a Child Welfare Committee (CWC) (Section-55) rehabilitation and social reintegration services for victims (Section-34), public awareness campaigns and educational programs (Section-37). Key milestones in the legislative developments in child protection in Bhutan include ratification to UNCRC (1990) [24] and its Optional Protocols on the sale of children, child prostitution, and child pornography (2009)[25], Child Care and Protection Act (CCPA, 2011), Child Adoption Act, 2012,[26] implementing the Domestic Violence Prevention Act (2013),[27] and execution of the National Plan of Action for Child Protection (2013–2018).[28] In fact, reviews by the Committee on the Rights of the Child identifying areas for improvement (2017),[29] and reports reflecting on the progress and ongoing challenges in child protection over the past decade also helped to shape the law enforcement.[30]

Nepal has progressively developed and modified its legal framework to address CSA and exploitation, culminating in the enactment of the National Penal (Code) Act, 2017 and the Act Relating to Children, 2018. These statutes delineate specific offenses and prescribe stringent penalties and criminalizes various forms of sexual offenses against children such as defines and penalizes rape in terms of the graveness of the offence committed (Section-219), criminalizing any sexual contact with a child under the age of 18, with prescribed penalties of imprisonment up to 3 years (Section-225), and prohibits "unnatural sex," which, while not explicitly defined, is interpreted to include non-consensual acts and carries significant penalties (Section-226).[31] The Act like Indian POCSO also explicitly delineates which acts constitute of child sexual abuse (Section-66), rehabilitation of victims (Sections-70-71), and a 3-tier Child Welfare Councils (Sections-59-63).[32] A timeline of legislative developments in Nepal revealed that it was the first country to ratify the UNCRC in 1990 [33] and enacting a Children's Act, 1992,[34] ratifies the Optional Protocol to the UNCRC on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution, and Child Pornography (2000),[35] and constitutional enshrinement of child rights (2015) and promulgation of the National Penal (Code) Act, criminalizing various forms of sexual offenses against children.

Maldives has progressively developed its legal framework to address child sexual abuse (CSA) and exploitation, reaching legislative landmarks such as the Special Provisions Act to Deal with Child Sex Abuse Offenders (SPADCSAO, 2009), the Sexual Offenses Act (SOA, 2014), and the Child Rights Protection Act (CRPA, 2019). These statutes delineate offenses, prescribe penalties, and establish protective measures to safeguard children. Interestingly, the SPADCSAO makes Maldives unique with its features such as establishes a structured monitoring system to oversee offenders even after they have completed their sentences (Section-2), graded punishment for different types of CSA (Section-3-6), higher punishment for individuals in positions of trust (15-18 years of imprisonment) (Section-9), and child prostitution and pornography (20-25 years of imprisonment) (Section-18).[36] Similarly, the Sexual Offenses Act (2014) delineates the punishment for the offence of rape (20-25 years of imprisonment) (Section-14).[37] The Child Rights Protection Act of 2019 (Section-11) also reinforces the prohibition of child prostitution and pornography, and Section-122-123 also mandate stringent penalties for offences such as grooming in child trafficking.[38] Thus, a timeline of legislative developments in the Maldives shows its ratification to the UNCRC (1991) [39] and Optional Protocol to the UNCRC on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution, and Child Pornography [40] ; enacting SPADCSAO (2009) in addition to implementing the SOA in 2014 and the CRPA in 2019.

CSA Legal Frameworks: Definition, Coverage, and Futuristic View: India and Nepal offer most expansive and comprehensive definitions of CSA, encompassing a broad spectrum of offenses such as grooming, child pornography, and non-contact abuses. Maldives introduces post-sentence monitoring of convicted offenders, though extremely important (as 70% are repeat offenders and the registry doesn’t provide optimum results) [41] but a measure not highlighted in other South Asian legal systems.

Mandatory Reporting and False Reporting: Due to low socio-economic status, cumbersome legal procedures, loss of daily livelihood for parents due to court case, the fallout of mandatory reporting by the healthcare professionals needs larger discussion. More research is required on the nuances of mandatory reporting in these countries. In general, studies from India on retrospective account of CSA are more from India in the region,[42] however, data on false reporting and disposal needs emphasis.

Punitive Frameworks reflect the prevailing socio-political-cultural scenario of these countries. Afghanistan criminalizes the practice of bacha bazi, imposing up to 10 years of imprisonment as a penalty, whereas Pakistan mandates a minimum sentence of 14 years. Bangladesh and India prescribe capital punishment for the most egregious CSA cases, rendering it one of the most severe sentencing frameworks in the region. The Maldives stipulates a minimum incarceration period of twenty years for CSA offenses involving child trafficking and pornography. Still punishment and career/vocational rehabilitation of the repeat offenders (<18 years) need more attention.

CSA Law- A Double - Edged Sword for Adolescent Boys: The legal provisions must consider the nuances of age and development related secondary sexual characteristics in children aged 13-18 years. Legal age for involvement in consensual sex and defining the legal interpretation of consensual both are very crucial in deciding punishment and any legal action. Due to lack of awareness and education pertaining to existing legal systems related to CSA, many adolescents aged 15+ years are trapped in the strict legal frameworks despite their own understanding of consensual sex between the partner that happened in the relationship. Parents of the girls remain in an advantaged position, whereas the life of the boy and his family could get ruined because of this unaddressed issue and as the burden of proof remains with the boy.

Age of Criminal Responsibility: It is lowest, 10 years, in Maldives. However, other countries need to specify.

Judicial and Procedural Protections: Nepal, India, and Sri Lanka have instituted child-sensitive judicial protocols to minimize re-traumatization and ensure the psychological well-being of victims during legal proceedings. Maldives’ specifically guarantees that child victims are shielded from direct exposure to perpetrators in courtrooms. However, despite the presence of strong statutory provisions, systemic issues continue to undermine the efficacy of legal frameworks. Factors such as societal stigma, victim-blaming, fears of familial dishonor, and cumbersome legal procedure deter to seek legal recourse. Furthermore, deficiencies in law enforcement training contribute to suboptimal investigations, while judicial inefficiencies, coupled with political and bureaucratic corruption, impede the prosecution of CSA cases across the region.

Rehabilitation and Victim Support Structures: This exhibits considerable disparity. Bhutan’s and Sri Lanka prioritize the rehabilitation of CSA survivors by establishing child-friendly shelters and psychological support services. Bangladesh mandates compensation and reintegration mechanisms for victims; however, challenges in enforcement persist. Strengthening victim protection frameworks and ensuring the sustained provision of psychological and social rehabilitation services remain imperative for long-term recovery and reintegration into society.

Case Disposal/Closure Time Period: Minimizing the case disposal time period is crucial for the victims and accused to move forward in life. Data is not available from any country.

V. POLICY IMPLICATIONS & FUTURE DIRECTION

The key considerations for South Asian countries to robust the legal frameworks of CSA are:

1. Legal definitions and protective measures concerning CSA must be expanded to encompass a broader spectrum of offenses, including online sexual exploitation and grooming, and sexual bullying at school.

2. Pakistan and Afghanistan should incorporate explicit provisions against non-contact offenses.

3. All nations should also clear their stand on punishment terms for repeated child sexual offenders.

4. Establishing a standardized regional framework, akin to Indian or Maldivian Act, would enhance legislative uniformity and facilitate cross-border legal cooperation.

5. Judicial training and law enforcement capacities require significant augmentation to ensure effective prosecution of CSA cases. Specialized task forces dedicated to investigating CSA should be instituted, complemented by advanced digital forensic capabilities to address the growing prevalence of online abuse.

6. School-based programs should be designed and prioritized to equip children with knowledge of consent, punishment, age of criminal responsibility, burden of proof, and reporting abuse.

7. School-curriculum in South Asia must contain contents on child abuse in general and CSA in particular even from standard-1 with a developmental sensitive approach.

8. Governments should make funding towards psychological counseling, secure shelters, rehabilitation and structured reintegration programs public.

9. Standardized culture-friendly protocols for conducting child-friendly interviews within law enforcement and judicial settings should be shared among countries.

10. Enhancing regional collaboration through cross-border cooperation mechanisms, particularly in cases of transnational child trafficking, remains critical.

11. Developing a centralized South Asian CSA offender database would significantly bolster monitoring efforts and facilitate the apprehension of perpetrators operating across multiple jurisdictions.

VI. CONCLUSION

South Asian countries have made commendable strides in strengthening their legal frameworks against Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) and child marriage, largely spurred by the ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, 1989). Significant progress is evident in the proliferation of applicable laws, increased public budgets, enhanced societal awareness, and the establishment of legal redressal mechanisms. The abolishment of archaic child marriage restraint laws has also played a crucial role in curbing CSA legally, though concerns persist regarding the continued practice of child marriage in certain nations like Bangladesh, Nepal, and Afghanistan. India and Nepal, in particular, have developed comprehensive CSA definitions, encompassing a wide array of offenses, while Maldives' post-sentence monitoring of offenders offers a unique, vital measure for addressing recidivism.

Despite these advancements, several critical gaps and inconsistencies persist, necessitating concerted efforts for a truly robust and harmonized regional approach. Discrepancies in the legal age of marriage across countries, and incongruences with the universally accepted definition of a child (0-18 years), continue to pose challenges. The absence of specialized courts for CSA cases in some nations, coupled with the socio-economic implications and lack of data on false reporting related to mandatory reporting, underscore areas requiring deeper research and policy refinement. Furthermore, the "double-edged sword" effect of CSA laws on adolescent boys, particularly concerning consensual sexual activity and the burden of proof, highlights a need for nuanced legal interpretations and greater awareness. Victim rehabilitation and support structures remain disparate, and a critical lack of data on case disposal times across the region impedes effective evaluation of judicial efficiency.

Moving forward, policy implications demand a multi-faceted approach. Legal definitions must expand to explicitly cover online sexual exploitation, grooming, and school-based sexual bullying, with Pakistan and Afghanistan needing to incorporate provisions against non-contact offenses. Establishing a standardized regional framework, augmenting judicial training and law enforcement capacities—including specialized task forces and digital forensics—are imperative. Prioritizing school-based education on consent, legal rights, and reporting mechanisms is crucial for prevention. Finally, enhanced regional collaboration, including cross-border cooperation for transnational trafficking and the development of a centralized South Asian CSA offender database, is essential for comprehensive monitoring and perpetrator apprehension. Only through such sustained, collaborative, and victim-centric efforts can the region fully realize its commitment to protecting its children.

*******

References

[1] UNICEF. “Sexual Violence - UNICEF DATA.” UNICEF DATA, 23 June 2025, data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/violence/sexual-violence.

[2] Hillis, Susan et al. “Global Prevalence of Past-year Violence Against Children: A Systematic Review and Minimum Estimates.” Pediatrics vol. 137,3 (2016): e20154079. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-4079

[3] ---. “Country’s Biggest Child Abuse Scandal Jolts Punjab.” The Nation, 8 Aug. 2015, www.nation.com.pk/08-Aug-2015/country-s-biggest-child-abuse-scandal-jolts-punjab.

[4] “Senate Passes Law to Criminalise Child Sexual Abuse.” DAWN.COM, 11 Mar. 2016, www.dawn. com/news/1245034.

[5] “The Revised Afghanistan Criminal Code: An End for Bacha Bazi?” South Asia@LSE, 24 Jan. 2018, blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2018/01/24/the-revised-afghanistan-criminal-code-an-end-for-bacha-bazi.

[6] “Afghanistan’s Child Sexual Abuse Complicity Problem.” Human Rights Watch, 2 Aug. 2017, www.hrw.org/news/2017/08/02/afghanistans-child-sexual-abuse-complicity-problem.

[7] BBC News. “Nato Denies Reports Troops Overlooked Afghan Child Abuse.” BBC News, 22 Sept. 2015, www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-34328398

[8] Ohchr.org, 2015, www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session28/Documents/ A_HRC_28_48_en.doc.

[9] Refworld - UNHCR’s Global Law and Policy Database. “2015 Trafficking in Persons Report - Afghanistan.” Refworld, 10 Feb. 2024, www.refworld.org/reference/annualreport/usdos/2015/en/106499.

[10] The Human Rights Situation of Children in Afghanistan: Violations of Civil and Political Rights – Rawadari. rawadari.org/181120231707.htm.

[11] Misra, Amalendu. “Men on Top: Sexual Economy of Bacha Bazi in Afghanistan.” International Politics, 11 June 2022, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-022-00401-z.

[12] Parliament of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. “Penal Code (Amendment).” Penal Code (Amendment) Act No 22 of 1995, 1995, citizenslanka.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Penal-Coda-_Amendment_-Act-No-22-of-1995-E.pdf.

[13] Sri Lanka. National Child Protection Authority Act, No. 50 of 1998. Government of Sri Lanka, 1998. https://childprotection.gov.lk/images/pdfs/acts-guidelines/National%20Child%20Protection%20Act,%20No.%2050%20of%201998.pdf.

[14] UNICEF. UNICEF Annual Report 1994. United Nations Children's Fund, 1994. https://www.unicef.org/media/93541/file/UNICEF-annual-report-1994.pdf.

[15] About NCPA | National Child Protection Authority. childprotection.gov.lk/en/about-us/about-ncpa.

[16] “Sri Lanka Struggles to Contain a Growing Epidemic of Child Abuse.” TIME, 13 Aug. 2013, time.com/archive/7149658/sri-lanka-struggles-to-contain-a-growing-epidemic-of-child-abuse.

[17] Legal and Policy Documents | National Child Protection Authority. childprotection.gov.lk/en/resource-centre/legal-policy-documents.

[18] Khan, Md. Emran Parvez, and Md. Abdul Karim. “The Prevention of Women and Children Repression Act 2000: A Study of Implementation Process from 2003 to 2013.” IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science (IOSR-JHSS), by IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS), Ver. 11, vol. 22, July 2017, pp. 34–35. www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol.%2022%20Issue7/Version-11/E2207113442.pdf.

[19] The Parliament of Bangladesh. The Prevention of Oppression Against Women and Children Act 2000. 14 Feb. 2000, iknowpolitics.org/sites/default/files/prevention_act_bangladesh.pdf.

[20] Bangladesh. The Children Act, 2013. UNICEF Bangladesh, 2013. https://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/sites/unicef.org.bangladesh/files/2018-07/Children%20Act%202013%20English.pdf.

[21] Bangladesh Migration Compact Taskforce to Ensure Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration. 5 July 2022, bangladesh.iom.int/news/bangladesh-migration-compact-taskforce-ensure-safe-orderly-and-regular-migration#:~:text=Bangladesh%20Migration%20Compact%20Taskforce%20to%20ensure%20safe%2C%20orderly%2C%20and%20regular,Compact%20for%20Migration%20(GCM).

[22] “In Bangladesh, Gaps in Laws Are Placing Vulnerable Children at Risk of Sexual Exploitation - ECPAT.” ECPAT, 6 Sept. 2022, ecpat.org/story/bangladesh-eco.

[23] Bhutan. The Child Care and Protection Act of Bhutan, 2011. National Commission for Women and Children, 2011.

[24] Dolkar, T. (2023). The Evolution of Alternative Care in Bhutan over the Last Decade and Way Forward. Institutionalised Children Explorations and Beyond, 10(2), 134-140.

[25] “United Nations Treaty Collection.” Treaties.un.org, treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY& mtdsg_no=IV-11-c&chapter=4&clang=_en.

[26] “NATLEX - Bhutan - Child Adoption Act 2012.”

[27] “NATLEX - Bhutan - Domestic Violence Prevention Act of Bhutan, 2013.”

[28] “Protection … for Every Child.” Unicef.org, 2018, www.unicef.org/bhutan/protection-%E2%80%A6-every-child.

[29] “Committee on the Rights of the Child Considers Reports of Bhutan.” OHCHR, 2017, www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2017/05/committee-rights-child-considers-reports-bhutan.

[30] Dolkar, T. (2023). The Evolution of Alternative Care in Bhutan over the Last Decade and Way Forward.

[31] The National Penal (Code) Act, 2017.

[32] Nepal. Act Relating to Children, 2018. UNICEF Nepal, 2018.

[33] “CRC Monitoring and Reporting to UNCRC – Child Nepal.” Childnepal.org, 2023, www.childnepal.org/ programs/crcmnruncrc/.

[34] “NATLEX - Nepal - Children’s Act, 2048 (1992).” Ilo.org, 2025, natlex.ilo.org/dyn/ natlex2/r/natlex/fe/details?p3_isn=30034.

[35] “United Nations Treaty Collection.” Treaties.un.org, treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src= TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-11-c&chapter=4&clang=_en.

[36] Special Provisions Act to Deal with Child Sex Abuse Offenders. 2009, hrcm.org.mv/storage/uploads/ 50wN8XqA/8lvb7rok.pdf.

[37] SEXUAL OFFENCES ACT. lethun.pgo.mv/storage/files/1719809621_5.%20Sexual%2 0Offences%20Act%20-%20English%20Translation.pdf.

[38] Maldives. Protection of the Rights of Children Act, https://lethun.pgo.mv/en/laws/f3f688a7-7c1c-433c-b5fa-51bcb61d9373.

[39] “United Nations Treaty Collection.” Treaties.un.org, treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src= IND&mtdsg_no=IV-11&chapter=4.

[40] “United Nations Treaty Collection.” Treaties.un.org, treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src= TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-11-c&chapter=4&clang=_en

[41] Sharma D, Kewaliya V. Expectation versus Reality: Sex Offender Registration in India and the United States. International Journal of Legal Information, 2024. 52 (1): 88-97. Doi:10.1017/jli.2024.19.

[42] Chacko AZ, Paul JSG, Vishwanath R, Sreevathsan S, Bennet D, Livingstone PD, John J. A study on child sexual abuse reported by urban indian college students. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022 Sep;11(9):5072-5076. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1081_21. Epub 2022 Oct 14. PMID: 36505616; PMCID: PMC9731069.